Identity / Identidad

In English?In this lesson we reflect on the many layers that make up Latinx identity. After examining a page of Jesusita Baros Torres’ citizenship study guide, we develop and write down our own ideas about the connection between the promises enshrined in the Constitution, and the many ways of being Latinx across the United States.

Learning Objectives

- Students will analyze a written text and establish a connection between the text and their own experience

- Students will develop a written argument in which they express their personal opinion about the multiplicity of Latinx experience in the US

In this lesson, we focus on…

- Literacy: Development of a written argument

- Language: Communicative functions of codeswitching

- Grammar: Use of imperfect subjunctive to make suggestions

Materials

- Digital image of cover of citizenship study guide belonging to Mrs. Jesusita Baros, Ft. Lupton CO, 1941.

- Digital image of page 20, citizenship study guide belonging to Mrs. Jesusita Baros, Ft. Lupton CO, 1941.

- Library of Congress Teacher’s Guide to Analyzing Books & Other Printed Texts (one-page handout) [pdf]

De muchos, uno

Lesson Plan Overview

- Antes de empezar

- Para continuar la conversación

- Mira otra vez, mira más de cerca

- Después de leer: ¡manos a la obra!

- Focus on Grammar

- Focus on Language

- Un paso más: en comunidad

- Down the rabbit, whole...

Antes de empezar

For Teachers

The focus of this instructional sequence is the diversity of Latinx communities, and the right of every member of these communities, regardless of generation of arrival, legal status, linguistic ability, socioeconomic condition, national origin, sexual orientation, physical ability or religious belief, to enjoy the rights enshrined in the Constitution of the United States.

Step 1. In class. Present students with the question: ¿Qué es el sueño americano? Write down answers on the board, and after every student in the class has answered in Spanish at least once, have them identify common threads: adequate housing, health, freedom of expression, opportunity, equality, good working conditions, etc.

Step 2. In class. Present students with a second question: Veamos las ideas que escribimos en el pizarrón ¿Éste es solo el sueño americano, o es en realidad el sueño de toda la humanidad? Help students make the connection that fundamental rights and wellbeing are a right and an aspiration of humanity.

Step 3. In class. Use three of the words written on the board to highlight the diversity of Latinx experience. For example, what might the right to form a family mean to a gay Latinx couple? What might access to healthcare mean to an uninsured diabetic Latina? What might economic opportunity mean to a recent college graduate as opposed to his immigrant parents?

Para continuar la conversación

For Teachers

In this activity, students read Libertad sin lágrimas, by Chicano poet Alurista. The class discusses the connections that can be traced between the poem and the topic of this lesson.

For Students

Alurista (Alberto Baltazar Urista Heredia), es un poeta fundacional de la literatura chicana, activista por los derechos civiles de las comunidades mexicanoamericanas y profesor universitario. El poema Libertad sin lágrimas, que ahora vas a leer, se publicó en 1971 y habla de la importancia de la dignidad, la libertad, y la autodeterminación para cualquier proyecto que tenga como objetivo el avance social, político y económico de estas comunidades.

Después de leer este poema sol@ o en grupo, hablemos de las conexiones entre el mensaje del poema y las ideas que escribimos en el pizarrón.

Libertad sin lágrimas

Urista Heredia, A. B. (1971). Floricanto en Aztlán. Chicano Cultural Center, University of California.

Mira otra vez, mira más de cerca

For Teachers

In this activity, students manipulate two digital objects from the Shanahan collection to learn about the experience of a Mexican American woman who lived during the first half of the Twentieth century. Using clues embedded in these images, they will deploy their background knowledge to make inferences about the ways in which historical period, gender, social context, legal status and economic standing helped to shape her aspirations. Students will also learn about the struggle of many immigrant families to integrate into the fabric of the communities in which they live.

After a brief introduction to the digital objects they will manipulate, students will be presented with a set of questions that will help them understand these objects and their historical context. Because you are more familiar with the proficiency level, profiles, and developmental needs of your own students, these questions are to be prepared by you, the teacher. A good resource to help you prepare these questions in a time-effective manner is the Primary Source Analysis Tool , published by the Library of Congress, and freely available in electronic or pdf formats.

For Students

Treinta años antes de que Alurista escribiera Libertad sin lágrimas en California, Jesusita Baros Torres estaba estudiando su guía para la ciudadanía en su cocina de Fort Lupton, Colorado. Jesusita Baros Torres nació en 1896 en el pueblo minero de Jalpa, Zacatecas, México, y emigró a Estados Unidos con sus dos hijos más pequeños en la década de 1920. Aunque no tenía papeles y no hablaba inglés cuando llegó, durante más de cuarenta años crió a su familia y fue parte activa de su parroquia, de su barrio, y de la comunidad mexicana de Fort Lupton.

El documento que tienes frente a ti es una reproducción digital del ejemplar personal que usó para prepararse para presentar su examen de ciudadanía. Esta guía se publicó en 1941, el mismo año en el que Estados Unidos entró en la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Como muchos otros inmigrantes antes y después de ellos, Jesusita y su esposo, Maximino Torres, invirtieron mucho esfuerzo, muchas horas y mucho dinero para regularizar su estatus migratorio. Para ellos, fue un proceso que duró más de veinte años. En 1976, cuando murió, Jesusita Baros Torres había vivido ochenta años, casi cincuenta de ellos en Estados Unidos.

Usa las preguntas que te va a presentar tu maestr@ para ayudarte a analizar estos dos documentos.

For Teachers

Present students with the set of questions you’ve prepared to help them work with these digital objects. Remember that you can save time and effort by using the Primary Source Analysis Tool , published by the Library of Congress.

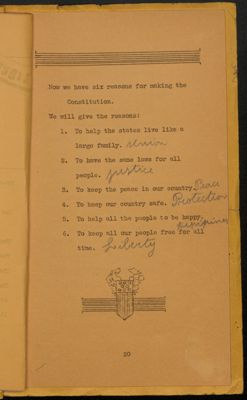

The Constitution

- Title: Citizenship study guide

- Identifier: shan.D005

- Date: 1905-04-24

- Format: Document

- Creator: N/A

- Held by: Elizabeth Jane and Steve Shanahan of Davey, NE

Cover and page 20 of typewritten and hand-illustrated citizenship study guide belonging to Mrs. Jesusita Baros, Ft. Lupton CO. In English, with handwritten notes in pencil. Lessons for adults (first level). On the preamble to the Constitution of the United States. Prepared by Northern Colorado Teachers of Naturalization of the Adult Education Program (1941).

Transcript of Cover

The Constitution of the United States of America. We the People. Book One. The Preamble.

[Handwritten in pencil]

Mrs. Jesusita Baros. Ft. Lupton, Colo.

Transcript of page 20

Now we have six reasons for making the Constitution. We will give the reasons:

- To help the states live like a large family.

Union [Handwritten in pencil] - To have the same laws for all people.

Justice [Handwritten in pencil] - To keep the peace in our country.

Peace [Handwritten in pencil] - To keep our country safe.

Protection [Handwritten in pencil] - To help all the people to be happy.

Hepipines [Handwritten in pencil] - To keep all our people free for all time.

Liberty [Handwritten in pencil]

Después de leer: ¡manos a la obra!

For Teachers

After completing the pre-reading activities and working with the digital objects selected for this lesson, students are assigned a one-page text in Spanish in which they present their opinion about the multiplicity of Latinx experience as related to the promises enshrined in the Constitution.

Speak with your students about the differences between the promises contained in the preamble to the Constitution and the lived experience of the most vulnerable in their own community. Present students with two or three questions that help them think about and develop their own ideas about this topic. Some examples: ¿Crees que existe una diferencia entre libertad de ser, libertad de hacer y libertad de pertenecer? ¿Qué quiere decir Alurista en el verso libres/albedrío of our own self assertion/and our will? ¿Qué quiere decir para ti libertad sin lágrimas? .

To be complete this task successfully, students texts will include a premise, inference and a conclusion, and will include at least three instances of conditional + imperfect subjunctive to express an opinion, desire or evaluation. Consider presenting students with a model.

Focus on grammar: Use of imperfect subjunctive to express opinions and desires

For Teachers

Before students begin to write their texts, briefly review the use of imperfect subjunctive to express opinions and desires.

For Students

Después de conversar sobre el tema de esta unidad, vamos a practicar nuestras habilidades de escritura en español. Regresa al texto del poema y a la página del manual de ciudadanía de Jesusita Baros Torres y piensa qué significan para ti las palabras que aparecen en el preámbulo a la Constitución. ¿Qué tienen que ver con las diferentes maneras de ser latin@ en Estados Unidos? Desarrolla tus ideas sobre este tema en un texto de una página.

Al escribir, no te olvides de usar la estructura que acabamos de revisar:

Lo que yo quiero, me gusta o recomiendo… |

Lo que va a pasar si se cumple mi deseo… |

Condicional |

Imperfecto del subjuntivo |

Verbos que terminan en -ía |

Verbos que terminan en -ara, -iera, -era |

| Me gustaría que... | supieras que l@s latin@s somos una comunidad diversa |

| Esperaría que... | todos disfrutáramos de los mismos derechos |

| Sería importante que… | Conociéramos mejor nuestra historia |

Focus on language: Communicative functions of codeswitching

For Teachers

In this activity, students learn about the communicative functions of codeswitching, as they practice locating information in a text, inference, and interpretation.

For Students

Para hablar de lengua: Funciones comunicativas de la alternancia de códigos

La alternancia o cambio de códigos (codeswitching, en inglés), es el uso de dos o más lenguas en el mismo turno de habla. Alternar efectivamente entre una lengua y otra requiere un dominio avanzado de la estructura de dos o más lenguas y es una competencia característica de las personas altamente bilingües. Además, requiere tener en cuenta factores como el entorno, el interlocutor, el tema de la conversación y la identidad étnica o social de quienes están hablando.

La alternancia de códigos es parte de lo que llamamos competencia bilingüe. Es un proceso diferente de la mezcla de códigos. La mezcla de códigos (codemixing, en inglés), es lo que sucede cuando estamos empezando a aprender una segunda lengua y usamos una palabra de nuestra lengua dominante para llenar una laguna léxica.

El translenguaje (translanguaging, en inglés), es una práctica relacionada, que ocurre en el salón de clases cuando un@ alumn@ que está desarrollando sus habilidades lingüísticas y académicas al mismo tiempo, hace uso de los recursos de sus dos lenguas para entender y comunicar mejor lo que está aprendiendo.

La alternancia de códigos puede cumplir diferentes funciones comunicativas. Por ejemplo, a veces cambiamos de lengua para repetir lo que dijo otra persona en la lengua en que lo dijo (función de discurso indirecto). A veces repetimos o enfatizamos lo que acabamos de decir (repeticiones e interjecciones), a veces cambiamos de lengua para comunicar un estado emocional (codificación de emociones), y a veces usamos dos o más lenguas al mismo tiempo para jugar con el lenguaje, para hacer arte, o para contar un chiste que solo es gracioso si entiendes las dos lenguas (función retórica o expresiva).

Después de leer

A. ¿Cuál es la diferencia entre la alternancia o cambio de códigos y la mezcla de códigos?

B. El uso del español y el inglés en el poema Libertad sin lágrimas

C. Alurista pudo haber escrito este poema solo en inglés o solo en español. En tu opinión, ¿qué quiere decirnos sobre su identidad al usar las dos lenguas al mismo tiempo?

Un paso más: en comunidad

For Teachers

In this extension activity, students establish a link between the topic of this lesson and Latinx experiences in their own community.

For Students

En esta actividad vamos a conectar el tema de nuestra conversación en clase con la experiencia de algunas personas de nuestra comunidad. Entrevista a dos personas que vivan en tu ciudad, que se identifiquen como latin@s y que pertenezcan a dos generaciones distintas. Antes de comenzar, explícales que estamos platicando en clase sobre las diferentes formas de ser latin@ en los Estados Unidos.

Paso 1. Prepárate para anotar sus respuestas.

Paso 2. Pregúntale a cada un@ qué es una cosa que le gusta hacer y que le identifica como individuo, una cosa que le gusta hacer y que le identifica como miembro de la comunidad donde vive y una cosa que le gusta hacer y que le identifica como latin@.

Paso 3. Después, explícale que vas a leerle seis palabras, y pídele que te diga la primera palabra que le venga a la mente después de escuchar cada una. Lee cada palabra de manera clara y pausada.

Estas son las palabras que vas a leerle a tu entrevistad@:

- Unión

- Justicia

- Paz

- Protección

- Felicidad

- Libertad

Paso 4. Con el permiso de tu entrevistad@, escribe su nombre, género, ocupación, edad y lugar de nacimiento. También escribe la fecha y lugar de tu entrevista (Recuerda que en español escribimos las fechas así: día, mes, año).

Paso final. En clase. Trabajando en grupos de tres. Escriban en el pizarrón las respuestas de sus entrevistados, organizadas por edad, género y lugar de nacimiento. Después de eliminar las respuestas que se repiten, observen las palabras que quedan. ¿Qué cosas en común notan? ¿Cuáles son algunas diferencias que les parecen importantes/interesantes? ¿A qué creen que se deban estas diferencias tomando en cuenta la experiencia de las personas que entrevistaron?

Down the rabbit, whole…

For Teachers

Down the rabbit, whole… is an optional activity designed to be informal, ludic, and open-ended. It involves students going on an internet rabbit hole with the intention of learning more about a seemingly minor detail presented in this lesson. This activity is also intended to reinforce students’ ability to discern between trustworthy and untrustworthy internet sites.

This activity has three rules, which may be modified to suit the type and goals of your class:

- The class or the group of students who will be playing (and not the teacher) agrees on a time limit (e.g. 10 minutes, half an hour, a class period, a week, a month).

- At the end of the agreed time period, rabbit hole travelers share what they learned with the rest of the group in an informal conversation in Spanish.

- Rabbit hole travelers show their work: What pages did they visit? What kind of pages were they? How many leaps (jumps from one site to another) took them to find the information they were looking for?

El poema que leíste en esta unidad habla de los “caballeros tigre”. Esta es una referencia a los ocēlōpilli, nombre náhuatl de los caballeros jaguar del ejército azteca. Consulta en internet y responde: ¿Quiénes eran los ocēlōpilli? ¿Qué características suyas quiere destacar Alurista en este poema? ¿Por qué crees que Alurista identifica a los jóvenes mexicanoamericanos de su generación con los caballeros tigre, y no con los caballeros águila?

More lesson plans